T. S. Eliot

1888-1965

“Love is most nearly itself When here and now cease to matter.”

Robert Lowell

1917-1977

Only in the last few years have I begun to truly appreciate this poet's work. He is a fascinating figure in American poetry and one of the most engaging readers of his own poems. I was invited into the subtle depths of his work simply by following his expressive voice and distinct accent. They led easily into the whispered corners and places he describes, imagines or re-invents with a masterful portion of soft intrigue. The beauty and imbalance of his masterpiece 'For the Union Dead' is rare in poetry. He holds a frame up for his painted words that sketch out several layers of time that seem to be fingers on the same hand. Another thing which attracted me to his work was the descriptive detail and the atmospheres, which are gently placed in small packets along the way. I was also drawn by the fact he had run a now legendary poetry workshop seminar that was partly responsible for the developing talents of both Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, among others – what a room that must have been. Lowell is an amazingly 'gettable' poet. Able to transfer images off the page and into the mind, following simple, yet subtly contrived and intertwining paths – '...a savage servility slides by on grease'.

“The dead season when wolves live off the wind.

Anne Sexton

1928-1974

These days, given her former stature, she is possibly one of the most underrated poets of the twentieth century. As I wander in my studies of various poets and their poetry, she seems overlooked, time and time again, It is possibly because she is a woman? An 'untamed' woman at that – 'Her Kind', who very often wrote about womens' subjects realistically and relentlessly. In the years between 1960 until her untimely death in 1974, she was incredibly successful and won the Pulitzer Prize among other accolades. She drew large audiences for her readings and was financially very successful, so far as poetry goes. Audiences loved her casual, relaxed, chain-smoking approach, and I suppose this financial success is part of the reason she is now somewhat discarded – people are suspicious when poets climb out of the water and sit by a pool in the sunshine – their own pool, at that – and paid for with poems – especially when one frequently deals in the subject of darkness, death and depression. In my opinion, the main reason for her success is the fidelity of her work. An amazingly effective output that would despatch that of most other poets. She was a tormented soul and she put it onto the page in a naturally alluring way, confiding with anyone who would listen – and what more can we ask of a poet than that? I believe she still has much more to offer than many of the current critics understand, or give her credit for. Amongst her poems, I recommend reading 'Her Kind', 'For My Lover, Returning to his Wife' and 'Flee on a Donkey'. This last poem is about a stay in a mental institution – for her, one of many.

“As it has been said: Love and a cough cannot be concealed. Even a small cough. Even a small love.”

Sylvia Plath

1932-1965

Is she the saddest story in the whole of recent poetic history? Or is it because she managed to become one of the all-time greats of poetry, before her time was cut so tragically short, or thereabouts, leaving her robbed of life and we, her listeners, robbed of poetry we might now only imagine? Having said that, it is hard to believe she could have continued in the relentless heat of the final fire in which she wrote and lived. Listening to the intensity of her readings can soon become uncomfortable. It is always as though death, having knocked once, has only gone down the road a moment and will call again soon. It is a long story, but Plath's soul was haunted by death, almost from her beginnings, and she seems to fizzle to a rapid end. It must be said though, that her mental health issues began long before the poetry became intense and well before she became involved with Ted Hughes.

Having had her first poem published when she was only eight years old, she seems set upon her course from an early age – a true poet, who did not just stumble into poetry through indecision or serendipity, she put the many required hours in from the beginning. Sylvia Plath was part of Robert Lowell's famous Boston seminar, where she became friends with another emerging poet with mental health issues: Anne Sexton. Setting aside the brilliant and insane Lowell for a moment in his role of mentor, it is incredible that two poets of this stature passed through the same room. In some ways, they are very similar, but these are overshadowed by the differences, which are vast. Sylvia Plath is slightly more direct, but in a much more brutal way – she understands, yes, but she is not having any of the thoughtful sidetracks. Plath demands things in her poems – demands truth, alchemy, discipline, practicality and most of all, she demands to be heard above the noise of her difficult life. My favourite poems of hers are 'Daddy' and 'Lady Lazarus'.

“let me live, love, and say it well in good sentences”

Wallace Stevens

1879-1955

I really like Wallace Stevens' work and his style, which is both rigid and searching in an effective way, though somewhat like the position often taken by Philip Larkin – one of an outsider – either looking in, or looking out – a taker of notes, with which to commute new facts to the fascinated reader, delivered with a gorgeously rich vocabulary and a sure-footed train of thought. Stevens rarely committed himself to any of the poems as a character or a traveller, and therefore presents himself as an observationalist in as perfect a position as possible – not particularly from an elevated viewpoint, but certainly of one who has risen from his seat to get a better look. I am not sure quite how he has been an influence on my own work directly, but just by the fact I like his work so much, it must render some sort of influence inevitable. There is at least one poem of mine where I felt influenced by his rigid, observational and statement-like work – my poem: 'The Mirrored Facade?' for instance. I recommend you read Wallace Stevens': 'Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour', 'So & so Reclining on her Couch', 'The Idea of Order at Key West' and 'Sunday Morning'.

“Throw away the light, the definitions, and say what you see in the dark.”

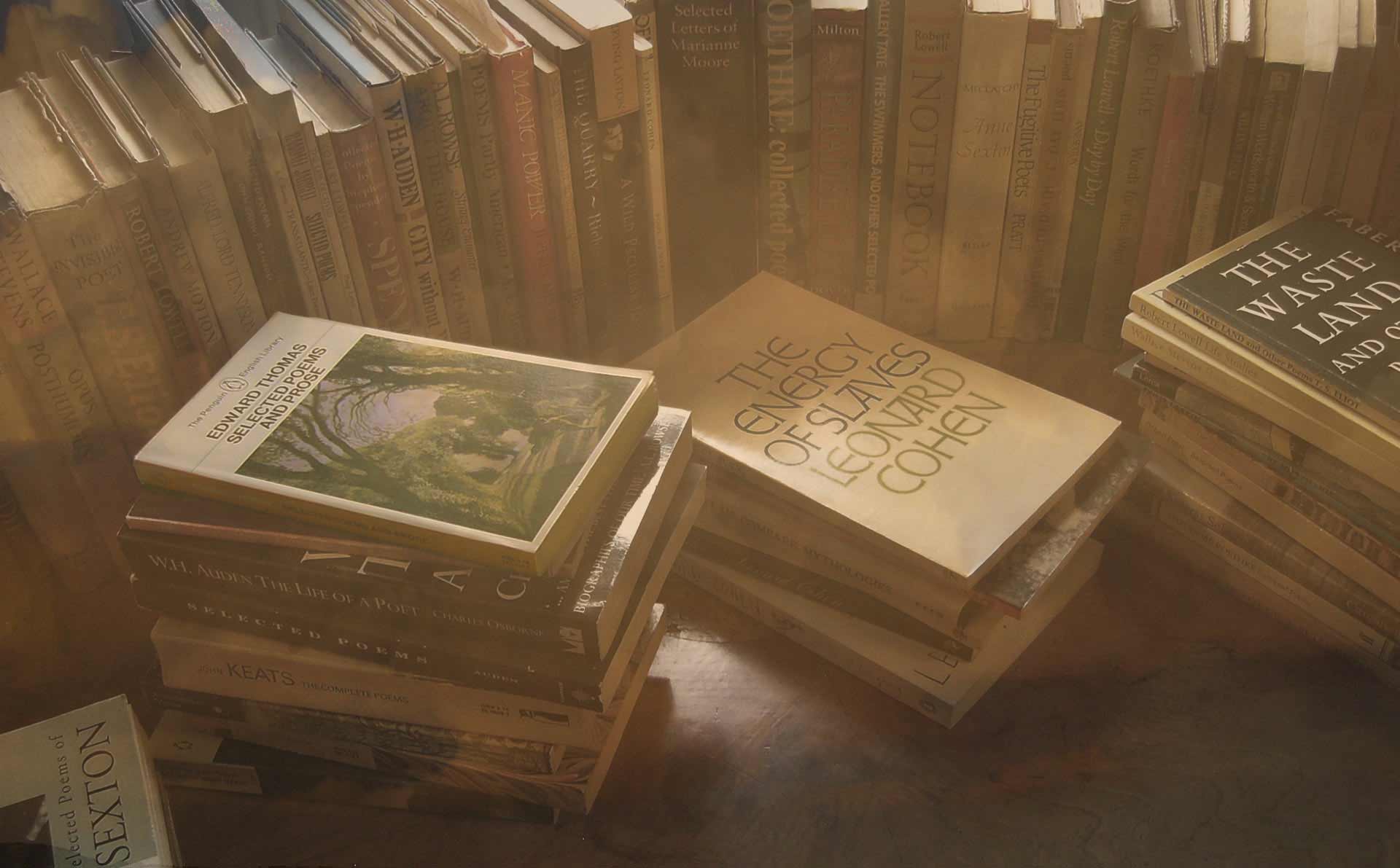

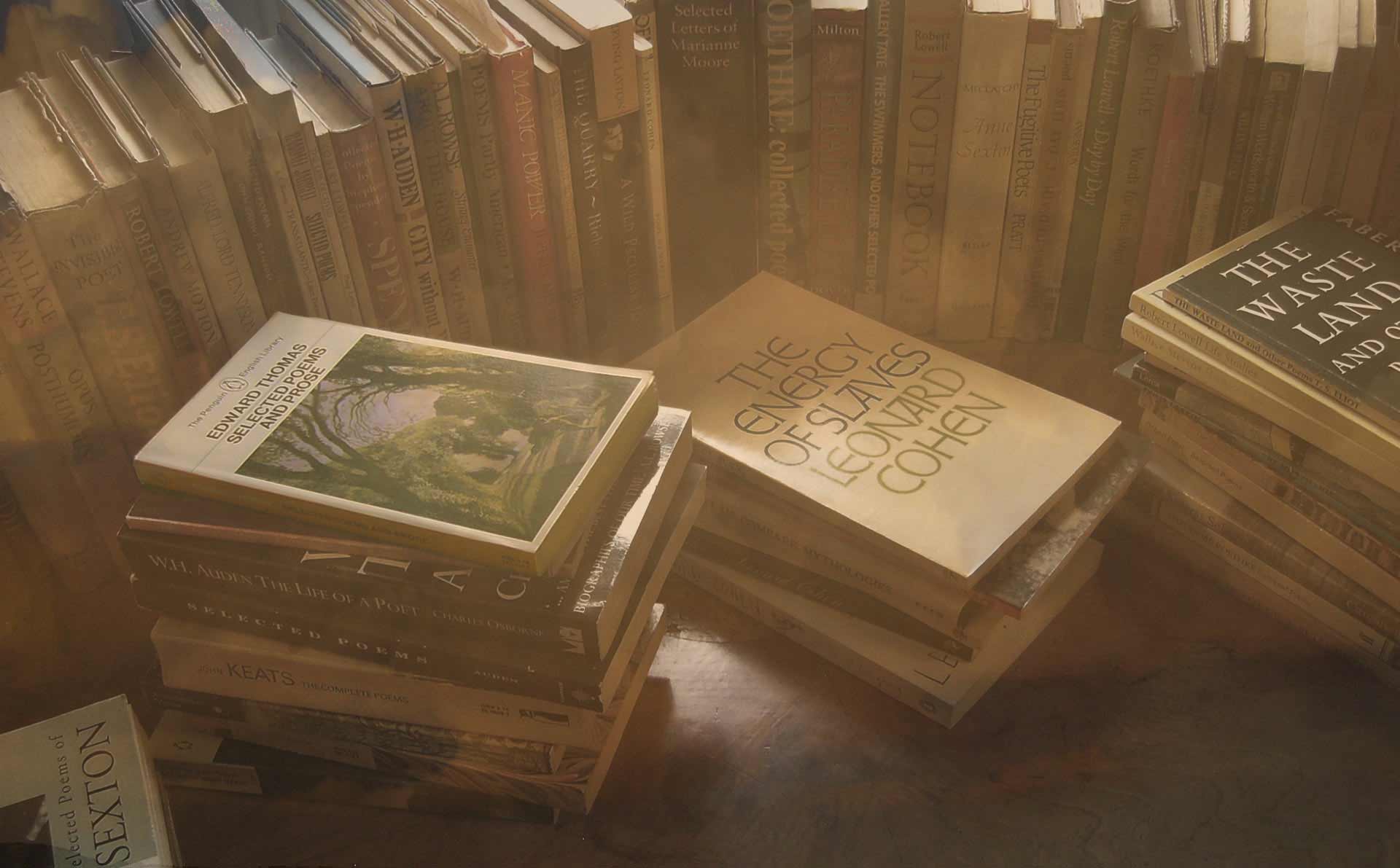

Leonard Cohen

1932-2016

As a teenager in the late nineteen sixties, I was more interested in writing songs than poetry. My influences then were The Beatles, Paul Simon, Bob Dylan and a few others. Then Leonard Cohen came along with his richly woven words that took songs to a place even Dylan could not reach. I was also drawn into his wonderful appreciation of chords and chord changes and for a while, I was diverted into a studious listening period that absorbed his songs like necessary vitamins. Later, I became interested in the man himself and who his own influences might be; I sought his poetry to find out. His words led me to the words of others, such as the Spanish poet, Federico García Lorca and Cohen's fellow Canadian poet, Irving Layton.

It can be said that Leonard Cohen was in many ways, my most important influence because without him, I may not have ventured into the realms of poetry at all. What I liked about his writing was the simplicity of his style – he spoke from the room he was sitting in and reached us, wherever we were, and seemingly without effort or the regard of distance or time. I think that still applies, his words still reach out from their valid place in music and literature. His shortest statements often hold such insightful comments on life. I soon went on to read his two novels, which contain some fabulous sheaves of creative writing, with a wonderfully perceptive flow that holds the reader's attention over some difficult terrain. At that time – he was the master and his song was the gospel from a necessary stranger:

"It's true that all the men you knew were dealersWho said they were through with dealingEvery time you gave them shelterI know that kind of manIt's hard to hold the hand of anyoneWho is reaching for the sky just to surrender."

So far as his poetry goes, I was initially stopped in my tracks by his fourth book of poems: 'The Energy of Slaves'. I saw it in a bookshop window in the city of Bristol in 1972 and bought it a few days later. Then I began to buy his previous volumes, which unfolded his genius, going more than ten years back into the 1950s. By the late 1960's he had largely abandoned his career as a poet for one leaning more towards that of a troubadour, which is pretty much the same thing, when in a setting of folklore and tradition, or the medieval past. But not quite in the last hundred years or so; music has lately been 'elevated' above its poetic roots into something quite different – with a simplified importance.

Throughout his career, Cohen observed an occasional affiliation with his printed roots and therefore seemed to share a stage with himself. In my view though, he cannot be seen as anything but a poet in either aspect. His best poems are often simple ones; they are extracted from invention, occasion, religion, sex and fantasy – all the covert processions that snake their way into the real world and squeeze some unnoticed truth out of it. It is a style that I was greatly attracted to as a young man – there is a noble spirit of rebellion, freedom, adventure, acceptance and disgust in those expressive words. I was also impressed by his humour. I think many people missed the humorous side of his words in the mesh and contortions of his generally serious posturing; people took Cohen far too seriously. Leonard Cohen was always there to entertain – first and foremost – and that ambition remains alive today in all his work.

Some of my favourite poems are these: 'Queen Victoria and Me', 'The Only Poem', 'I Try to Keep in Touch', 'Poem' and 'Days of Kindness'.

"There is a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in.”

Philip Larkin

1922-1985

I have a lot of time for Philip Larkin – he is one of the great English poets. While alive and writing, he found a relatively large audience, and pretty much without trying, though his profile was almost on a parr with Betjeman, who worked very hard in his bestowed public roll of Poet Laureate to publicise himself through the media of television, which broadened into his own interests, such as travel and architecture. Larkin in comparison, was almost a recluse, certainly as far as the wider public and literary circles where concerned. He placed himself out of sight, on the eastern edge of England, ensconced in the fishing port city of Kingston upon Hull. It was a place he did not particularly like – an arrangement that probably suited his lugubrious spirit.

Being head librarian at the university library at least afforded him a fingertip on the literary scene – looking over the fence at it and as close up as he wanted to get. As added camouflage, he looked as much like a head librarian as anyone ever has – a balding, oval-faced man with an habitual frown. This image, with nothing else to draw on, became a perfect label for him – the rigid, gloomy librarian poet, but of course, there was much more to Larkin behind his facade.

He was never truly comfortable with himself and in approaching Larkin as a person, and also when reading some of his poetry, readers need to understand that ‘the past is a very foreign country’ – not that Larkin would have appreciated visiting foreign countries, he had reached his epiphany on that score in Hull, with its appropriate level of alien discomfort. What I mean is that times change and measures of expectancy change with it. Larkin may appear to be brutally honest and totally outrageous to some of the more mellow modern ears, that for all their reducing left-wing freedoms, have become almost inert and cannot take the complications of engrained reality as they are now, let alone how they were. I find it frustrating though that this can so easily lead to Larkin's instant dismissal as a writer. People of any age can seem ignorant of time and place these days – even those who are clearly very intelligent. Some seem to have to award themselves the unnecessary badge of ignorance, partly as a need to score kudos-points amongst their peer group, or some other perceived audience. Larkin was a true poet and therefore full of exploitative beliefs and concerns and he was likely to voice them in an attempt to understand them himself. He was also perhaps surprisingly capable of juggling the attentions of two or three women at a time and these women provided a loyal friendship that could only be based on fascination or respect.

While filming a documentary about Larkin, the then poet laureate, Sir John Betjeman said “If anywhere is the end of England and the end of land, it is Hull and beyond." Ironically, it was through earned statements like these, aimed through the valuable presence of Larkin that had put that place – the place at the end of everything – on the map. I even worked there myself for a short while, just before Larkin died.

When Sir John Betjeman died in 1984, Larkin was offered the role of Poet Laureate, which he promptly turned down, saying he no longer produced new work and was therefore redundant as a poet. It is a pity, because the role would have for once been held by a great poet and one that also had the common touch. After he declined, the role was given to the translucent poet, Ted Hughes. When Larkin died, a few years later, the Times obituary said that he was 'the most widely read and appreciated poet of his generation'.

Some of Larkin’s poetry may seem negative, but as he said himself, writing a poem is not a negative process and is a positive thing, and this idea therefore cancels the other one out, so far as Larkin's character is perceived. It was often said that he was not particularly contemporary – but the trick is to be timeless and it seems to me that his work is exactly that, a mission often found complete in its sheer simplicity. He was very disconnected though, partly on purpose and something like the character and the positioning of Wallace Stevens. The sense of his own wistful isolation is at its most powerful in the poem: ‘The Whitsun Weddings’. He is the consummate observer, sometimes seeming to ridicule or dismiss, but all the time there is a sense that he is exploring the situation and seeing where he, himself, might fit in. The imagery of the final line of that poem has often been discussed, certainly by Larkin's friend and biographer, Andrew Motion. My own take on this is that the arrow-shower is emblematic of these many marriages taking place that day, simply sent forward by their own inertia from the braking train – fired off with invisible bows into the future – with a wonderful sense of beauty, love and hope, but typically, as is Larkin’s lugubrious way, their initial mood of sunshine and optimism will at sometime in the future, inevitably breakdown and become rain – and given the divorce rate, who would deny that possibility?

'And as the tightened brakes took hold, there swelledA sense of falling, like an arrow-shower Sent out of sight, somewhere becoming rain.'

Larkin was a master of these deceptively simple, reverse mood endings that leave lingering questions, as at the end of 'Talking in Bed’: 'it becomes still harder to find words at once true and kind, or not untrue, and not unkind.' And again at the end of ‘Reasons for Attendance: 'both are satisfied, if no one has misjudged himself. Or lied.'

“What will survive of us is love."

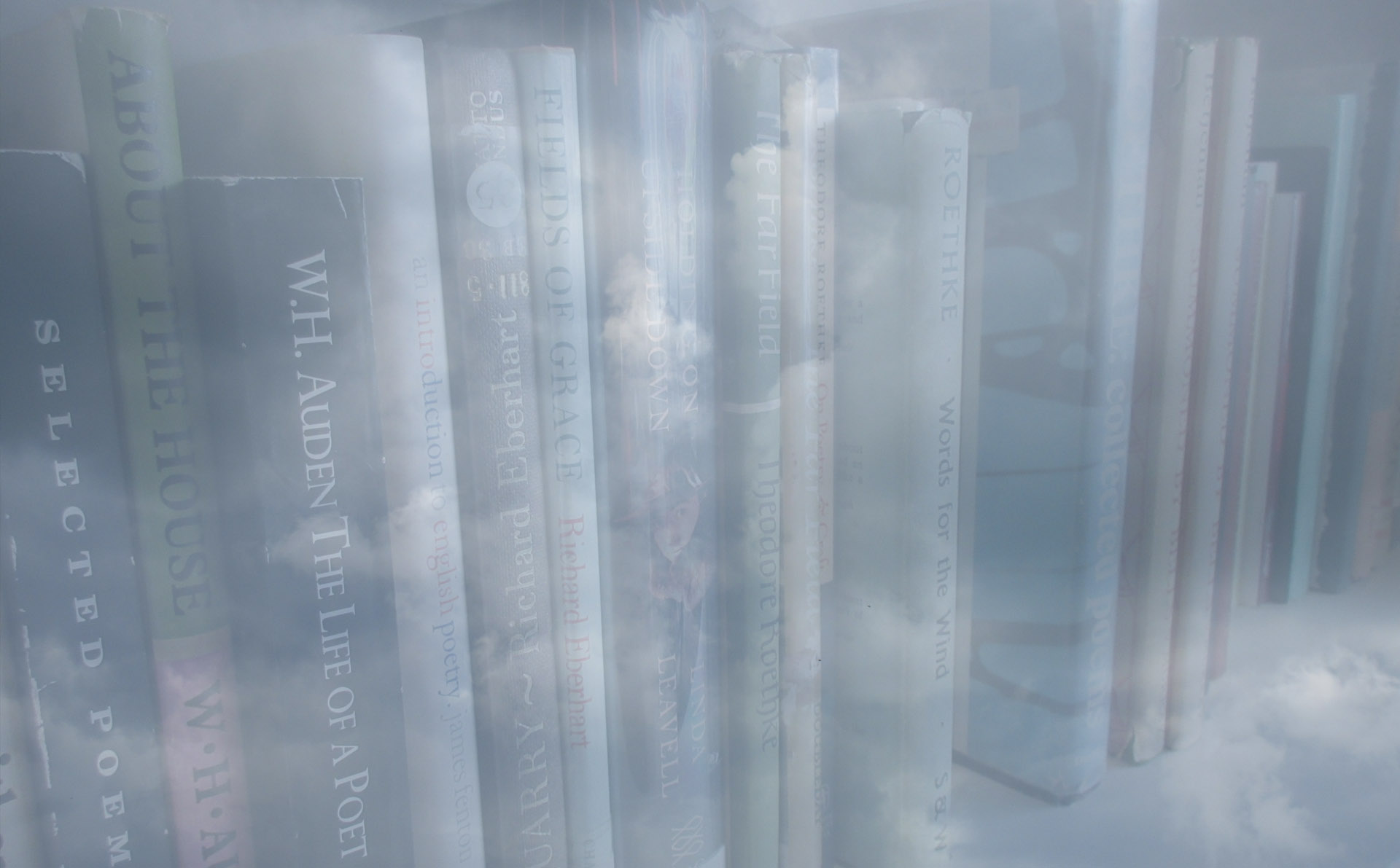

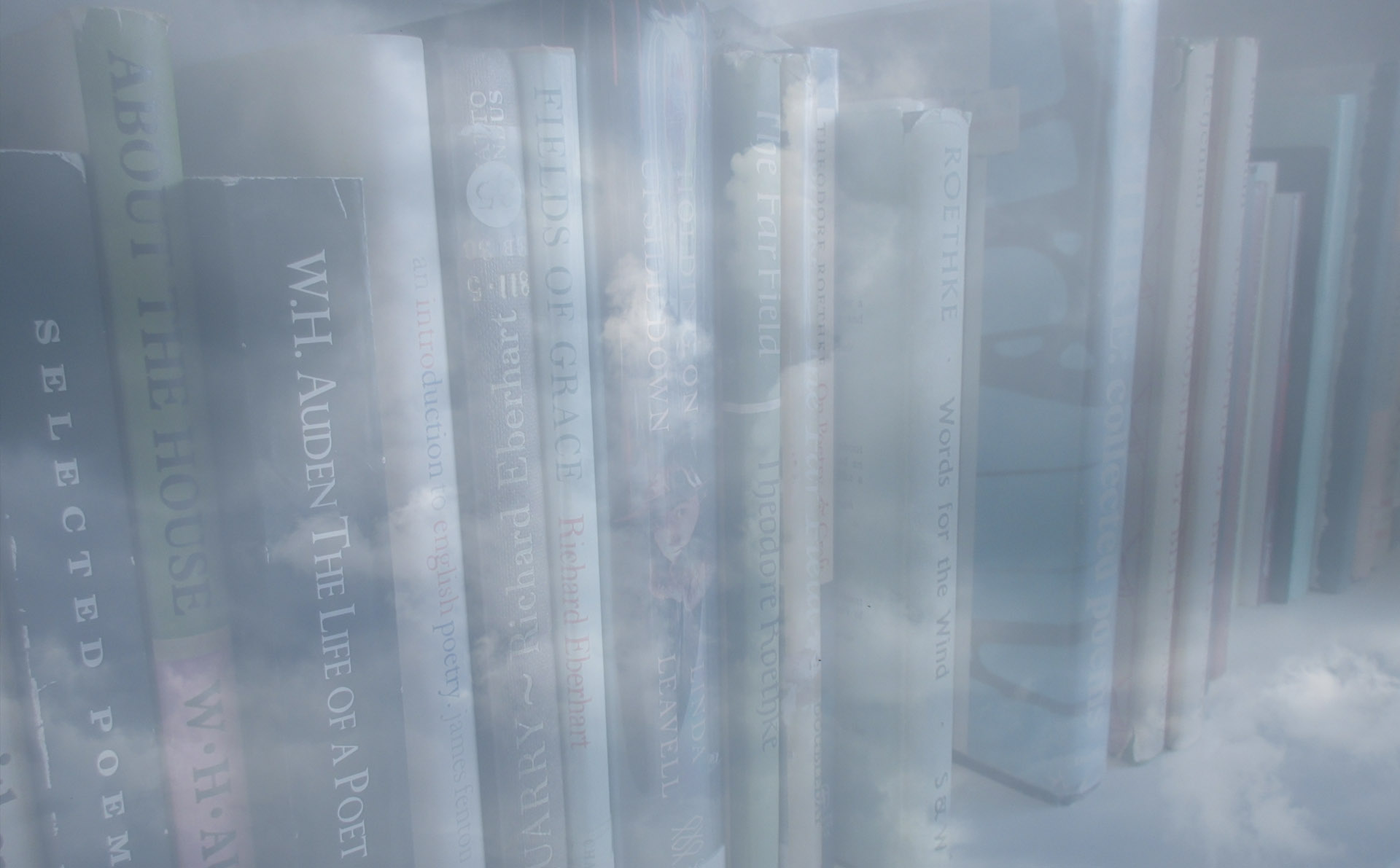

Andrew Motion

1952 –

I have a lot of respect for Andrew Motion. He was a friend and biographer of Philip Larkin, and also wrote a biography of Keats. This, in part, is one of the attractions for me about him. I very much like his honest, academic and practical view of poetry, which I think has helped him build the backbone of his own work. He has a great understanding of other poets and more importantly, a great interest in them and in the general tradition of poetry. I think this is why I am sighting him as one of my own influences. I too, in interrupted phases throughout my life, have studied the work of other poets and this interest has increased in recent years, partly because for much of my life I have been engaged in the visual arts, where I made my living. I have now committed myself to writing for the foreseeable future and I hope there is time left to fulfil my extensive plans. In some ways, I feel I have been in poetic exile, though at the same time, I cannot imagine my whole life being spent in poetry. It seems a very wearying and enclosed idea – even stifling. I would say to most poets, stop chasing phDs in poetry and literature, unless you are Theodore Roethke or Robert Lowell, get a job outside the subject – the experience will free your mind and soul. I am only saying this because I was born the same year as Motion and I can't imagine myself being engaged in poetry for all that time, even though I have written several books worth of poetry. In truth, I have never tried very hard, or very specifically to get my work published – it has been an ongoing experiment – almost a diary of adventure. In fact, my first poem did not appear in print until recently – forty-five years after I began writing.

I first became interested in Andrew Motion when he stepped down from the role of Poet Laureate, thus freeing his own soul, I suspect – and perhaps making a louder statement than his quiet persona lets on. It is an unusual occurrence for Poets Laureate to step down or agree a limited term of office – in fact, as far as I am aware, it had never happened before. Most of the previous Poets Laureate vacated the office only when they died and in most cases, that was not soon enough. Being Poet Laureate is a poison chalice, seemingly without form or structure, but is nevertheless reportedly very stressful; mostly because of the games the news and media play every time there is a moment of Royal interest. Having to write about a fixed subject and at a certain time seem to me to be nothing to do with poetry at all. In fact, it seems rather like my old job in advertising and marketing, though I did learn a lot about people; about their light and dark sides and also about human longing and their willingness to play roles against their better judgment. Motion's friend, Philip Larkin, was suggested as poet laureate when Sir John Betjeman died, but he turned it down and is quoted as saying something like: "Why would I want to go around pretending to be me?"

I am glad Andrew Motion stepped down from the role, I am sure the world will benefit now he is free to work without that far too open door. I think he has the touch and humility of a great poet about him.

“Honor the miraculousness of the ordinary.”

Theodore Roethke

1908-1963

This American poet is one of the great, eccentric characters of poetry. He had a natural enthusiasm for literature and for the teaching of it. He came from the sudden shock of a disturbed environment when, in his fourteenth year his father died of cancer and his uncle took his own life. These men, immigrants from Germany, had run a horticultural establishment in Saginaw, Michigan – a full twenty-five acres of greenhouses. It is this special contact with nature and his sense of abandonment, that spawned the deeply rich searching soul present in so many of his poems, and also his tendency to have one eye always attentive to the earth and its wonders. One of his most famous quotations is: "Deep in their roots, all flowers keep the light." As interesting a description of himself as anything else.

My own interest and study of poetry comes from my personal excavations. I have never had a formal course in literature and because of that, I have been able to look wider and deeper and wherever the flow takes me. There have always been thousands of poets, just as now, so one takes a very meandering path studying as I did. I was initially attracted to Roethke when I read about the distance relationship he had to two of my other influences, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, in the form of them all being nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in 1967 (Plath and Roethke were nominated posthumously, and Sexton won, but that's a whole different story). I also began to take a deeper interest in Roethke and his work, when I heard film director, Oliver Stone, read another of Roethke's excellent quotations in the commentary of the movie, JFK; a quote from perhaps his most famous and most anthologised poem. It was the line: "In a dark time, the eye begins to see." Then I discovered a wonderful film available on YouTube, with the same title as the poem. Watching this, it is hard not to fall in love with the guy. Since then, I have delved more deeply and have certainly been inspired by his energy and the radiant affection he grew in his art. He was a troubled man who suffered deep depression and mental difficulties. Given my own dealing with depression, I have always been interested in the way such experience can be passed to others in a positive way and discussed to the benefit of all. Many of my own poems deal with the subject of depression.

“Deep in their roots all flowers keep the light.”

Sir John Betjman

1906-1984

I think John Betjeman was an incredibly underrated poet, who at the same time, managed to become one of the most well known and popular poets England has produced. He was a rare and cherished man, who won the hearts of the nation with a carefully manicured and an almost comic eccentricity. It had at its core a precise vision. He loved Victorian architecture and real places and showed us a retrospective world of peace with a well-balanced sense of governance, all delivered through his well-loved mannerisms and charismatic presentation. However, it was often a real place he was trying to preserve through skillfully shining a spotlight on its wonders and often, on its impending doom. Whatever he touched along the way, particularly through the media of television, it seemed to live a little longer at least. In this way he made his tenure as Poet Laureate work with an unusually effective broadness, including as he did, the poetry of real architecture and infrastructure.

His poetry has broadly been described as 'light verse' but there is often a deep soul hiding within it. Behind the humour we can often find a deep sentiment or turn of phrase that is loaded with melancholy and wistful desire. Some of my favourite poems by Betjeman are 'In a Bath Teashop', 'Death in Leamington' and 'Crematorium'. In truth, it is hard to say why I have included Betjeman in my list of influences, but he was certainly there in the back ground of my thoughts for perhaps the most of my life. In fact, in the 1990s, my partner and I, Lara Newton, were so moved by the comedy and pathos in his work, we wrote a pastiche collection – possibly still a candidate for publication. Lara and I also went on to renovate a large Victorian House, so maybe the influence was stronger than I think. Another of his poems worth looking at is the autobiographical work: 'Summoned By Bells'.

"Too many people in the modern world view poetry as a luxury, not a necessity like petrol. But to me it's the oil of life."

Edward Thomas

1878-1918

He is often categorised as a war poet, but I see him as more of a bridge between the still archaic sounds of the dying age of Georgian poetry to the modern poetry, championed by T. S. Eliot and others. In fact, he is almost in a category of his own, given his limited burst of poetic writing at such an iconic time. He has also been called an early existentialist, mainly because of his awareness of his own individual alienation that often manifests itself in his work. Thomas's poetic career was very short, writing his first poems in 1914 at the age of thirty-six, undertaken at the insistence of his friend, the then unknown American poet, Robert Frost. This was a year before Thomas enlisted in the British army. He wrote his last poem three years later in 1917, before he was killed at the battle of Arras. His first book of poems was being printed at the time of his death, so he never saw much of his work published, except a few poems in an earlier pamphlet which did not bear his real name.

Although there are a few poems of his that can be considered to be about war, or eluding to it, it might be truer to say that he was driven and killed by his own depression – his low opinion of himself – and by a poem of all things that he received from Robert Frost. It was intended to lightly mock Thomas for his indecisive tendencies, a trait which Frost had noted when they went on their long walks together through the English country-side, before either of them were established as poets. The poem was the now famous: 'The Road Not Taken’, and it is highly probable that on receiving this poem, Thomas finally decided to enlist, though that effect was not intended by Frost, who wanted Thomas and his family to join the Frost family in America. There was no other pressure for Thomas to enlist, apart from that common urge of patriotism in his own head – he was a thirty-seven year old married man with three children at the time. A jaded writer of reviews and general hack work, though greatly respected as a reviewer, and one who frequently championed poetry. It is all such a pity – his creative spirit had only just been reawakened through the encouragement of Frost and who knows what other contributions he would have made to poetry had he survived the war. But perhaps 'our time' is all their is – both before and after the flame burns? Looking at the history of poetry and other aspects of human life, it is easy to believe in some planned intervention with its seemingly incumbent cruelty – we being only required for the minutes of our fulfilment and no longer, which is sometimes a belated requirement, not even attached to its own time.

Thomas's one, direct poem about the war – the rather stiffly titled: 'This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong' – is mainly an attack on the 'fat, god-like' leaders and the jingoism of the press, who have helped so many wars light up over the years. In the end, he seems to have taken the view that his beloved England was at risk and if nothing else, she was worth fighting for, and in thinking so, one naturally (reluctantly) makes an enemy. The last lines are these:

The ages made her that made us from dust:She is all we know and live by, and we trustShe is good and must endure, loving her so:And as we love ourselves we hate our foe.

"As well as any bloom upon a flower I like the dust on the nettles, never lost Except to prove the sweetness of a shower."

Emily Dickinson

1830-1886

She is one of those fairytales that get forgotten in the darkness of their own story, then emerge again, like someone holding their breath out of deep water. After she died in 1886 her friends and family published a short collection of her poems, though they revised them here and there, removing her ubiquitous use of dashes and applying normal punctuation as they saw fit. Her poetry was all but forgotten then, until the mid-nineteen fifties, when she was rediscovered and her true genius recognised for the first time. In fact, in my humble opinion, and speaking without conventional authority, she may well be the greatest American poet of the nineteenth century – she certainly ranks at the top of the list.

She left upwards of 1700 poems behind her and although her subject is prominently to do with aspects of death, it is partly 'the death in life' with all its concerns made transparent. The words are often full of exploration, great hope and wishful thinking. I was mainly attracted by her understanding of how hope seems to be inevitably contradicted by death. Without an afterlife, there is only death. The pursuit of happiness, freedom and knowledge, unless they can be passed on, seem suddenly pointless – even without the aid of depression. In later life, she seems to have worn only white clothes, maybe as a symbol of some kind, though not necessarily of purity. I like to see it as a mark of resistance against death itself and death's preoccupation with black.

I have made short films of a number of readings of Emily Dickinson's poetry, read by myself. They can be heard on this site in the video section.

“I dwell in possibility…”

John Donne

1572-1631

I first noticed John Donne when I was in my early twenties. I had studied graphic design and photography for the five years straddling the end of the nineteen-sixties and the beginning of the seventies. It was there that I became interested in poetry and I spent most of the rest of the seventies studying it and learning to write. In fact, I wrote four books of poetry during that decade, including some sonnets in an Elizabethan style and an epic poem of about two thousand lines; none of which I made a proper attempt to publish. I mention this because it has not always been the way for people to seek publication of their poems. In John Donne’s time it would have seemed vulgar and to some extent below the etiquette of higher social circles to seek publication of these often intimate thoughts and experiences. Apart from elegies, or poems in praise of other poets or persons, poems were more often than not given to friends and lovers, or read aloud at social gatherings. Donne, a courtier and adventurer, only had a handful of poems published during his lifetime and his work did not find an enthusiastic following until the early twentieth century – three hundred years after it was written.

For my own part, I have been incredibly lazy about publication and over protective of my work and this natural trait tends to prevail: even now I still have many digital art images and poems that remain unseen – nothing to do with etiquette, of course, some people are just made that way. Back in the seventies, I was also reading short stories and novels and I came across John Donne after finding the complete poem ‘No Man is an Island’ on the title page of my Penguin paperback version of Hemingway’s novel ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’. This one poem, deeply impressed me. It was like an ancient voice speaking to the now in perfectly acceptable language and terms, and in doing so, it seemed to me as though the poet had reawakened himself. Eliot and Hemingway were only just dead and still speaking to us, but with Donne – there was a distance of three hundred years and that shone a new light on the way I viewed time and art and the necessary, or accidental longevity of it all, and of all my other heroes of falling history, such as the brilliant Leonardo da Vinci and Beethoven. ‘No Man is an Island’, spoke to the isolationist I had become since leaving college and it made me feel part of some great tradition and it certainly encouraged me to continue as an artist and writer. I must say that I found Elizabethan verse in general difficult and archaic back then, but certain poems stood out and resonated with me, if perhaps only years later. One such poem is Donne’s: ‘The Good-Morrow’.

“Death is an ascension to a better library.”

William Blake

1757-1827

I was probably introduced to William Blake when I was at school, in my junior years. I vaguely remember being taught about his poem: 'The Tyger’; presumably with its accompanying illustration by Blake himself, drawn in his uniquely animated style, which has helped to lodge it in my memory. Not surprisingly, the words stuck too and I can clearly remember being impressed by such lines as: 'What immortal hand or eye / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?'

Blake is remembered as a visionary, as much as a poet, bearing forth poetry that was driven by religious urgency – the urgency of 'repent' – not towards christianity and the established paradigm though, but the 'repent' of dissidence – in order to find that final truth still lying undiscovered in the hearts of men – that constant light that shines back against the false and treacherous sun and faces it down with a new, more reliable light from within. Although his art and words are now regarded as genius, Blake himself is still an undiscovered profit-like soul – not much loved in is own time.

In my earlier days, my mother was forever suggesting that I combine my own art with my writing, but I always saw the two things as separate entities and I strongly believed that poems must drive their own imagery from their words – I explained this on a number of occasions and I still believe it now, even though I have made a number of short films to go with some of the readings I have recorded, which appear on this site. If it is not quite a mistake to tether words to imagery, I think we must be very careful in doing so. There is not so much a unity formed, as a trade off, and the poems may well be weakened by it rather than enhanced. We should all be allowed to see the pictures that we naturally conjure in our own heads – such as Blake's 'dark, satanic mills.' We may find a mill to photograph or to paint, that looks dark and satanic according to our particular values, but the phrase in the poem will always awaken a different spark in the electrical pulses of our brains and they will, of course, vary from one reader to the next. I suppose I may have contradicted myself here, but I mean to say that if imagery is to be used, it might be best to keep it vague or abstract. It may be that in employing imagery, we will do a better service to visual arts rather than the written words we seek to promote.

“If a thing loves, it is infinite.”

© Peter Hague | contact | terms and conditions

Design and photography @2020 Peter Hague Concept – Design – Art Direction and e-brink.co.uk Also peterhaguephotography.com